The worst kind of cookbook is one whose recipes just don’t work, of course. A close second is a database of recipes with no context, explanation, or personal story—recipe as equation that will give as clockwork and uninspired a result as a multiplication table. The kinds of cookbooks I love are personal, passionate, and preface each and every recipe with enough detail to know why it mattered to the cookbook author to include it, and how to judge the results as the reader and cook.

But even that kind of cookbook is primarily a tool—for expanding one’s repetoire of flavors or skills or simply grasp of how the other half eats. I’ve concluded, though, that my most favorite cookbooks are something beyond tools. They are what I hereby officially dub Narrative Cookbooks.

A Narrative Cookbook is not a Memoir with Recipes—a fine genre, and have I mentioned lately that I myself have written a Memoir with Recipes?—but its distinct own thing. In a Memoir with Recipes, the primary purpose is to tell the personal story, and in this particular case the personal story is very much bound up with food, so the author would like you the reader to taste or at least imagine the taste of the food that informed the life.

By contrast, a Narrative Cookbook is still more about the food than the life, but it recognizes that you can’t extract the one from the other, and the food won’t come to life without the life itself being reported alongside the recipe.

In my entirely unscientific survey, I find that Narrative Cookbooks span a spectrum from most essay-ish to most memoir-ish and the whole range in between.

Pride of place in the essay-ish Narrative Cookbook goes to Laurie Colwin’s two volumes, Home Cooking and More Home Cooking. Their tone is intimate and even a bit conspiratorial, letting you in on some delightful find or remarkable disaster and then winnowing out the culinary payoff for your own delectation. Chapters in the first book, for instance, include “Alone in the Kitchen with an Eggplant,” “The Same Old Thing,” “How to Avoid Grilling,” “Repulsive Dinners: A Memoir,” and “Easy Cooking for Exhausted People.” The recipes within each little gem of an essay are wonderful. I once served her roast chicken on polenta and broccoli rabe to a cranky person with whom I had an adversarial work relationship, and it smoothed things over almost magically. Her Country Christmas Cake from the second book is, I assure you, a fruitcake that people will actually eat—in fact, mine was so popular that I had a special request to make it as a wedding cake! It’s that good.

Another pair of essay-ish narrative cookbooks are more recent and less famous but also delightful: Jam Today and Jam Today Too by Tod Davies. Her tone is equally intimate and, though loosely organized into ingredients or sections, is more like a running commentary on meals she’s made. Even to call them recipes is too rigid for what’s she’s after: as the subtitle of the first says, “A Diary of Cooking with What You’ve Got,” these two little books are more like kindly mentorship in how to get good food on your table without resorting to takeout. You do learn bits and pieces about Davies’s life, including how she the carnivore manages to co-eat with her Beloved Vegetarian Husband. But mostly it narrates cooking, and then thinks about cooking, in a way that makes you want to cook more. As I have become less slavish about obedience to recipes, I find I like her approach more and more. It helps, of course, to already have amassed some serious kitchen skills. But at some point you need to be told it’s OK to launch out and try following your own kitchen instincts, and Davies has helped me do that.

And though I won’t go into detail about the already adequately lauded Nigella Lawson, I suspect a good portion of her success as a cookbook writer is the intimate, flexible tone that narrates its way through the recipes. In her latest, Cook, Eat, Repeat, about half the recipes are embedded in the prose anyway. You actually have to read the book to find the recipe. I find myself more drawn to these anyway—because it’s really cook talking to cook, not cookbook author performing for cookbook editor/marketing team.

Switching over now to the memoir-ish side of the spectrum, we come to two spectacular entries in the tragically short-lived Modern Library Food collection.

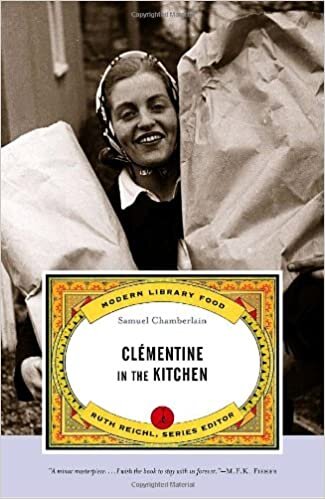

I first read Clémentine in the Kitchen by Samuel Chamberlain some years ago, and it must have been in that phase when I just did not get the big deal about la cuisine française because I liked the tales well enough but had no use for the recipes. Having just reread it—and now five years after moving away, feeling homesick for beloved Strasbourg—I wish I could move back for a term and cook all of them. Clémentine is a sweetly comic tale of shameless gluttony on the part of the Beck family (a lightly fictionalized version of Chamberlain’s own) who are converted to the glories of the French provincial kitchen in the 30s by their Burgundian cook, who is of course Clémentine. Yes, there are some inconvenient political developments in 1940 that force them to depart France for New England, but the story quickly gets back to the really urgent question: can you actually prepare French food in small-town Massachusetts? Clémentine is more than equal to the task—in fact, so equal to it that she lands herself a husband and leaves the Becks bereft. (But we are told that Mrs. Beck has learned so much in twelve years of eating Clémentine’s food that she goes on to be an accomplished French cook herself.) So yes, there are lots of stories and good rich characters in this book, but it is hardly a memoir by the achingly sincere and self-exposing standards of today, and in the end it really is all about the food. I suggest you buy a copy and then move to Burgundy. It will all make sense once you get there.

In the same aforementioned series is Wanda L. Frolov’s Katish, Our Russian Cook, another loving portrait of a family cook. This family, however, is not rich, and Katish is a cook somewhat by accident—she’s in fact an early 1920s refugee of the Russian Revolution, foisted upon a single mother and her two teenage children by the relentless do-gooding of an aunt worthy of P. G. Wodehouse. The affectionate portrait of Katish as a person (an extraordinarily convivial and generous person) revolves around her conversion of this mainstream American family in southern California, which shows no signs of gourmandise, into voracious appreciation of Russian classics. This, too, I wish I could take with me on-site and recreate each and every dish. Though for the time being I would settle for an affordable source of sour cream in Japan.

And this brings me to the last of my survey, Midnight Kitchen by Ella Risbridger. Here we are definitely veering to the far end of the spectrum and almost spilling over into today’s achingly sincere and self-exposing standards for memoir. Risbridger talks about her broken childhood family, her flight to the arms of the Tall Man, her temptations to suicide and extended depressions, and the tragedy of the Tall Man’s untimely death of disease. But here’s why I still qualify it as Narrative Cookbook rather than memoir of recipes: first, because after reading it a few times I still can’t quite get all the details to add up, and if the primary purpose were memoir a lot of the hazy stuff would have been clarified, and two, even the most painful memories serve to highlight the joy of the food and how cooking brought Risbridger back to herself and to life again. And with good reason. Wicked Stepmother Bread and seedy Danish Crackers are already favorites in my not-wracked-with-pain household, and my son makes his own Milk Bread every week for his school lunches. We could not quite rally around the Whisky and Rye Blondies, however charmingly named, but anyone who includes a recipe for Parkin is a friend for life, as far as I’m concerned.

Thus far my survey of Narrative Cookbooks. If you know and love another title, please drop me a line and let me know! I need more of these in my reading-and-cooking life, for sure.