This is the third in a series of three posts defining the key genres published by Thornbush Press. If you like what you read here, hop on over to the main Thornbush site and have a look at the catalogue!

I can remember the first time someone told me about Gabriel García Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. “It’s magical realism,” he told me. “What’s that mean?” I asked. The answer: “There’s a priest who levitates when he drinks hot chocolate.”

That was enough for me. I was hooked. You can guesstimate when this conversation took place based on the fact that I ended up reading the book in my private berth on an Amtrak traversing halfway across the country because all the flights were shut down due to a terrorist attack on the Twin Towers.

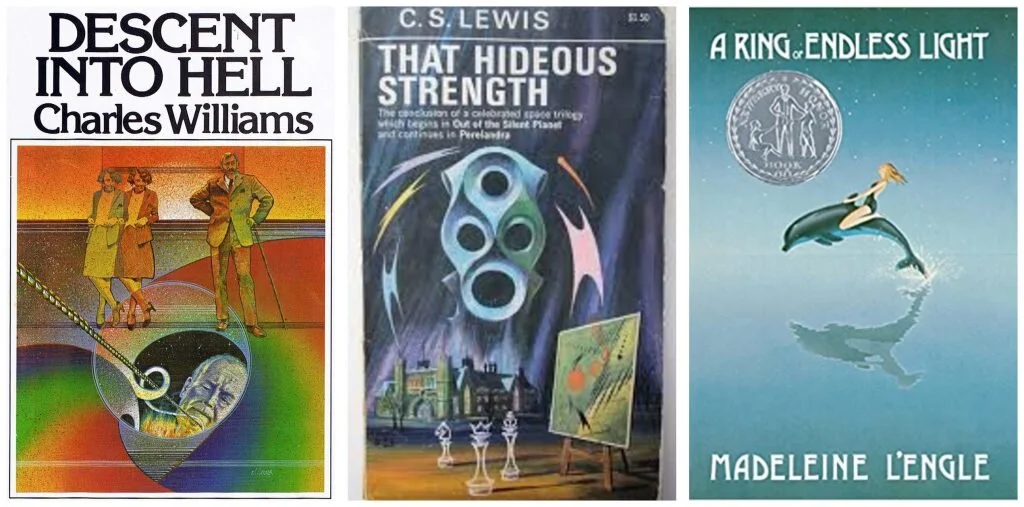

Marquez’s fiction has a distinct flavor all its own (of hot chocolate?), but it wasn’t so far off from other books I’d known and loved but had no collective term for. Top of the list was C. S. Lewis’s That Hideous Strength.

I did not start out loving this book, probably because I was too young the first time I read it. But more importantly because the trilogy structure inadvertently misled me. Out of the Silent Planet takes place on Mars! Perelandra takes place on Venus! That Hideous Strength takes place on… Earth?! I was bitterly disappointed, that first time through.

But subsequent rereadings shifted its status from my least favorite of the trilogy to my very favorite of all of Lewis’s works. It spoke to the intuition that there is much of a wondrous nature even on this Earth. The problem is not wonder’s absence but my (and our) perception thereof.

In the same way, much as I enjoyed A Wrinkle in Time, the novels of Madeleine L’Engle’s that I’ve reread and loved the most are The Arm of the Starfish, The Young Unicorns, and A Ring of Endless Light. All three remain on terra firma but strew wonders across the paths of the characters.

Much later in life I stumbled onto Charles Williams, whose fiction is virtually unclassifiable and regularly violates the rules of storytelling and yet somehow manages to work. Platonic forms descend, Tarot cards speak, doppelgängers haunt, ancient stones defy the laws of physics, and all these reveal spiritual character.

It’s hardly by accident that these three authors were professed Christians and wrote out of and toward their faith. But having never come across a satisfactory term for what distinguishes their fiction from that of other Christians, I’ve decided to coin one: mystagogical realism.

Mystagogy is a term from the early church, most associated with St. Cyril of Jerusalem and his “Mystagogical Homilies.” It means the process of inducting or teaching (hence the -gogy like in pedagogy) the mysteries of the faith. Catechumens to the church, before baptism, would be brought into the full range and meaning and practices of Christianity as preparation for the sacrament.

C. S. Lewis conceptualized his Narnia books in something of this fashion, as a kind of protoevangelion or preparation for the gospel. And certainly the wondrous tales of the not-tame lion have done that for many. But the sad truth is that none of us have actually managed to find a wardrobe with everlasting winter on the other side of the fur coats. Which suggests to disappointed adults that divine life might prove to be just as fictional as the Chronicles of Narnia.

Hence the other half of the term, “realism.” These are wonders that do not require an exit from reality to be experienced. More than that: this kind of realism counters the other claimant to realism which is really just nihilism in disguise. Mystagogical realism disputes faith in the abyss of nothingness that believes itself to have the upper hand, scientifically, philosophically, and ethically.

What ultimately got to me about That Hideous Strength is that for all the fantastical elements—Merlin, oyéresu, a decapitated head kept alive artificially—it reads like something that could happen, however much events lie at the edges of human experience. Same for the dolphins in L’Engle’s A Ring of Endless Light and the generation-spanning, time-reversing power of substituted love in Williams’s Descent into Hell.

There’s a red thread connecting these contemporary works with earlier ones like The Divine Comedy (Dante almost certainly thought that hell and purgatory were physically accessible to humans, following the best science of his day) and even Pilgrim’s Progress, which for all its allegory is meant to be perfectly realistic.

But I would go so far as to say there is no red thread connecting these classic and contemporary works of mystagogical realism to so much of what falls under the label of “Christian fiction.” Just as there is no discernible connection between the cantatas and passions of J. S. Bach and the latest release of “Christian rock.”

And that’s because there’s a difference between a mystery and a secret. A secret can be known, and once known, withheld and/or exploited. The worst kind of dispensationalist “Christian fiction” does not believe in God but in the time stamp on the ages and thus how to get yourself on the right side of history, lest you get left behind. In a world of secrets, advantages are zealously guarded and faith is actually the acquisition of arcane knowledge like, say, the relationship between the holy grail, Mary Magdalene, and Da Vinci’s Last Supper—much more exciting than repentance and forgiveness, that’s for sure.

But secrets are not mysteries. Even if they say they’re mysteries, even if they require faith, even if they strew angels, demons, thrones and principalities every which way, they are actually rationalist to the core. They are explicable and possessable and controllable. As such, they are the enemy of art and Christian faith alike.

Mystery is limitless. Mystery can be plundered and yet renew itself endlessly. A secret loses its secret-quality the more people know it. A mystery in inexhaustible and can embrace hosts of seekers without any diminution to itself.

The greatest of all mysteries is the God who loves sinners. The God who strews wonders before our feet, knowing that most us will trample them underfoot without even noticing. The God who gives himself up to death and abandons himself and then comes to himself in the depths of hell and raises himself up to new life. The God who keeps the wonder of creation going, deferring the end, because the unfolding story remains so wondrously good despite the horrors it still harbors.

That’s why mystagogical realism is a genre of such potency for our late-modern world, disenchanted of mystery and yet more susceptible than ever to secrets. It is not a genre that pretends humanity hasn’t gone through the convulsions of modernity and technology and science and democracy and totalitarianism. It doesn’t require believers to unknow what they’ve come to know. It is not a genre of pat and tidy happy endings, because it knows that the great and glorious happy ending is far beyond any middle-term human tale. It is not a genre of deus ex machina, because it professes instead the deus e sepulcro.

Love is real. Grace is real. Mystery is real. Mystagogical realism is the fiction that transforms the reader’s perception to behold the reality that’s been trampled underfoot.

Watch this space! Works of mystagogical realism are coming soon from Thornbush Press.