I’m pleased to announce that sometime this week I’ll have a new book out, Nenilava, the Prophetess of Madagascar, from Wipf & Stock. My co-editor Jim Vigen was a missionary in Madagascar for many years and met the great lady himself; I only learned about her secondhand, but you can’t visit Madagascar or the Malagasy without hearing all about her! This new book is the fruit of our combined labors to bring her story to the West. To whet your appetite, here’s my hagiography of Nenilava. Proposed date of commemoration: August 1.

Young Volohavana kept having dreams—powerful, moving dreams—but she could not understand them. Nothing in her small farming village along the southeastern coast of Madagascar could explain what she was seeing.

The dreams started when she was ten. A tall man placed her in a basin of water and washed her feet. After drying them, he rocked her gently to sleep. In another dream, he caught her in a net and then led her up to heaven. In yet another, he brought her to a church and up into the pulpit. He preached and told her that one day she would do the same.

Sometimes the dreams ceased altogether but then, during the day, she would hear a voice calling her name. At first she thought it was her parents, but they denied it and worried she might be losing her mind. She sensed somehow that the voice of the divine was calling out to her, but she didn’t know how to draw nearer to God. She gave up playing with other children and sat alone under a tree, weeping for want of God’s presence.

It wasn’t only the lack of God that troubled Volohavana. Her father Malady was a diviner with a widespread reputation. For pay he would consult with spirits through his oracle and offer wealth, zebus, children—whatever the heart desired. But Volohavana was not impressed. She doubted the power of the spirits; she mocked her father’s work, sometimes even in front of clients.

Worse yet, as her marriageable age came and went, she refused all the many qualified suitors asking for her hand. In desperation Malady turned again to his oracle, but this time the spirits gave him a very different kind of answer. “A superior Spirit, a God supreme dwells in her, and causes her indifference toward marriage,” they told him. “You, you are a slave, but Volahavana is a queen.”

At first Malady was baffled. After all, he himself was not of a royal lineage, nor his wife, so how could Volohavana be? But at last he discerned the truth: not blood but the Spirit of almighty God made Volohavana a queen. At this, Malady realized that he could no longer worship and collaborate with the spirits. He instructed his whole family to abandon their idols and serve Volohavana’s God alone. Yet there was no clear path to doing so: Volohavana’s call to serve arrived ahead of the church itself.

It was indeed no less than a finally successful suitor who brought the Gospel to Volohavana and her family. Mosesy Tsirefo was an aged farmer, widowed with several children, and about forty years Volohavana’s senior. He was also a catechist. After much badgering by her parents, Volahavana agreed to marry him—but first she had first to receive catechetical instruction and be baptized. She learned her lessons in record time, a mere two weeks, upon which she was baptized, received the baptismal name Germaine, and joined Mosesy’s household as his wife.

The dreams and voices long since having fallen silent, Volohavana might have led quite an ordinary Malagasy life after that. But on August 1, 1941, something happened that turned her life upside-down—and would prove to change the lives of thousands, quite possibly millions, of others in Madagascar.

By this time Christianity had been in Madagascar for about sixty years, and the Lutheran church in particular had already welcomed three revivals characterized chiefly by an active lay ministry of prayer and exorcism. As it happened, one of Mosesy’s own daughters was troubled by an evil spirit, and a catechist named Petera was struggling mightly to cast it out, to no avail.

Volohavana was tending the fire in preparation for the midday meal when a voice prompted her, “Get up and act upon this child.” She froze and dared not move, but the voice did not allow her to hesitate and propelled her out to where the girl and Petera were. Volohavana took Mosesy’s daughter into her arms and strove against the spirit, and at last the spirit gave up. It said, on departing, “We are leaving, for One who is stronger than we are has come.” The girl was healed.

That same night, Jesus appeared to Volohavana, Mosesy, and Petera, saying to them: “Get up, preach the Good News to all creation. Expel the demons. Commit yourselves and do not delay. The hour has come when the Son of Man must be glorified among the tribes of the Matitanana and the Ambohibe. I have chosen you for this mission. I command you to carry it out.”

Mosesy and Petera consented at once. Volohavana did not.

She embarked, in fact, upon the first of many quarrels with Jesus. Her first objection was that she was too young. Though her date of birth is not certain, she was no more than in her early twenties at the time of her call, and she’d been Christian only a very short while.

Moreover, being illiterate, she could not read the Scripture and therefore, she claimed, she could not preach. Jesus proved to be as obstinate as she was, however, commanding her again and again, “Get up and proclaim the Good News everywhere.” In the end Nenilava haggled her way into an acceptable compromise: as long as Jesus told her in advance what to say, she would do it.

Furthermore, because Jesus’ was not the only spiritual voice to which Volohavana was attuned, she asked him for a sign by which she could be certain to distinguish his call from false ones. He in turn promised that whenever he appeared he would display the stigmata in his hands, for no one could truly imitate them.

Even once she accepted the call, Volohavana was not immediately sent out on her mission. First she had to undergo a rigorous training program under the direct supervision of Jesus.He began by teaching her to speak in multiple foreign languages—twelve in all. He spoke and she repeated after him; he wrote vertically on white surfaces with white letters that were nevertheless visible to Volohavana. This went on for a period of three months, both in her home on Mosesy’s farm and out in the surrounding forest.

Next came instruction in Scriptures, but for this Jesus transported Volohavana to heaven. There Jesus taught her the four Gospels, starting with an explanation of the difference between a chapter and a verse—so ignorant was she at first of written Scripture. Then he walked her through each book, verse by verse, interpreting as went, just like on the road to Emmaus.

Seven times this happened, but the first time was accompanied by a dramatic sign. Jesus told Nenilava that she would die the following Friday at eleven in the morning. She shared the news with the church council, and word circulated so quickly that parishes far and near sent representatives, lay and clergy alike, to pray for her.

On that Friday morning, in preparation, the gathered assembly read the Scripture, prayed, and sang. Volohavana lay on a bed prepared for her, covered with a white linen but leaving her face exposed. When the hour came, she died quietly. The assembly did not leave her side or bury her but continued to fast and petition God for her return.

On Sunday morning at eight she arose, climbed off the bed, and pronounced the words of I Corinthians 15:55, “O death, where is your victory? O death, where is your sting?” After this the genuineness of her call was widely acclaimed, and each subsequent sermon further confirmed it: her words were too wise, too powerful to have any source but Jesus himself.

Yet Volohavana was still not quite ready to undertake her calling. One last test remained: to do battle against the beast. Reminiscent of both St. Michael fighting the dragon in Revelation, and early church martyr Perpetua’s visionary battle with an armed Egyptian in advance of her passion in a Roman arena, Volohavana faced the beast to test her strength for the mission ahead. Combat lasted three days and was brutal. The creature resembled a crocodile covered with spines, which sank deep into Volohavana’s flesh and tore it apart. Its tail beat her and tried to knock her to the ground. Because she refused to move from her kneeling posture of prayer, the beast could not make her fall; furthermore, Jesus had laid hands on her and promised her, “Be not afraid, I am your strength. From now on, you will defeat the beast.”

For three days she fought the beast, four times each day. At the end she was wounded and exhausted, and for a month she remained dazed and fatigued.

But from that point on, people began to bring to her their sick, their paralyzed, their needy: everyone who needed deliverance. And by the power of Jesus, she gave it to them.

In most places she was welcomed, but a faction developed, jealous of her new status. Looking for a way to taunt and discredit her, they fixed on her remarkable height: over six feet tall. Hence the name Nenilava, which means “tall mother.” But as has happened so many times before—not least of all with the name “Christian” (Acts 11:26)—she took the taunt as a badge of honor. It became her common appellation and is the name by which Volohavana is now known to Madagascar and the world.

The pattern for her ministry of deliverance got established right at the beginning and remain unchanged for the rest of her nearly sixty-year mission. She always began with preaching on a passage of Scripture. She exhorted the people to recognize and confess their sins in true repentance before Christ. The release that came with speaking the truth of their own evil deeds unleashed profound emotion and weeping, thereby preparing the people for the next stage, the casting out of evil spirits. Afterwards, those who desired it could receive the laying-on of hands, accompanied by what Nenilava called a word of comfort, encouraging each individual to trust in Jesus and so receive his blessing.

Although all four aspects together took place at every one of Nenilava’s evangelization campaigns, exorcism attracted the most attention and dispute. A wide range of opinions existed, from missionaries’ doubt as to whether demons existed to local insistence that every single pagan by definition required exorcism. A further debate concerned whether a baptized Christian could be possessed by an evil spirit. The consensus that emerged was that those who did not know Christ, or were Christian in name only, may be afflicted by the presence of evil and thus benefit from an exorcism.

Regardless of their religious affiliation, the people who attended Nenilava’s campaigns were always exhorted by her to repent. Often she named the sins directly to the sinners, as had been revealed to her by Christ. Both victimization by evil and collaboration with evil had to be overcome by Jesus. Non-Christians, indifferent Christians, and committed Christians all came to hear Nenilava and receive Jesus’ healing through her, leaving whole, healthy, restored to their families and restored to God.

For about thirty years after her call to service, Nenilava traveled around Madagascar, even as far as the Comoros Islands, to preach, exorcise, and bless. In due course a community sprang up around her in the village of Ankaramalaza, where her by now deceased husband had owned a plot of land. This became a toby, a revival center or camp, populated by pastors, exorcists, and those seeking their care. It proved to be the first of many that sprang up all over Madagascar, including one named for Nenilava herself in the southernmost town of Fort Dauphin. Ankaramalaza remained the spiritual epicenter, however, and the custom soon developed of Nenilava’s followers gathering there on August 1 and 2 every year in commemoration of her call, and soon, the consecration of new exorcists.

Called mpiandry in Malagasy, these “shepherds” undergo two years of training with their locals pastors before they are consecrated to their ministry. Even once consecrated, they do not preach, teach, or exorcise apart from the supervision of the local congregation, assuring that church and revival remain tightly linked to one another. Both women and men become shepherds, sharing all aspects of the work, and during their services dress entirely in white. Many live at the tobys, but none receive pay for their work, nor are the supplicants charged. Under Nenilava’s direction, the tobys also became important centers for medical and psychiatric care.

From the early 1970s onward, health problems limited Nenilava’s ability to undertake traveling campaigns. She went abroad twice, once to Norway and America, and another time to rural France to help train Malagasy immigrants who hoped to establish their own toby in Pouru St. Rémy, which finally broke ground in 1997. But mostly Nenilava remained at the toby in the Ambohibao neighborhood of Madagascar’s capital city, Antananarivo. Nevertheless, even there she continued to receive a steady stream of visitors, praying for them, casting out the spirits, calling them to repentance, and even arranging marriages, often between people of very different social and ethnic status.

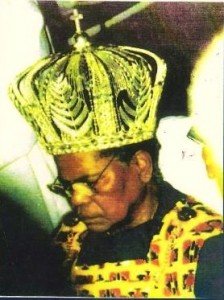

After a lifetime of unleashing surprises and provoking controversies, in 1983 Nenilava performed for her most controversial act of all. Jesus had long instructed her to receive consecration as a prophetess—an order that she had also long ignored, insisting that it would discredit her in the eyes of others. But at last she felt she could refuse Jesus no longer. She commissioned a robe and crown in the exact design of the high priestly garments of Aaron as described in Exodus 28–29. One of the pastors in her movement worked with her to compose the liturgy of investiture and performed the rite. While many people, understandably, expected the worst of this apparent bid for authority, Nenilava’s behavior underwent no change thereafter. She simply continued as before, referred all miracles to Jesus alone, and received every last person who came to see her.

Nenilava died in 1998 at the Ambohibao toby. Her body was taken to Ankaramalaza and buried within the toby walls there. Although saints are normally consecrated on the date of their death, the church in Madagascar commemorates her, and consecrates new shepherds to continue her ministry, on August 1, the date of her call into ministry.