A pastor and social reformer who dedicated his entire life to an utterly insignificant mountain village, and yet impacted the world. Proposed date of commemoration: June 1.

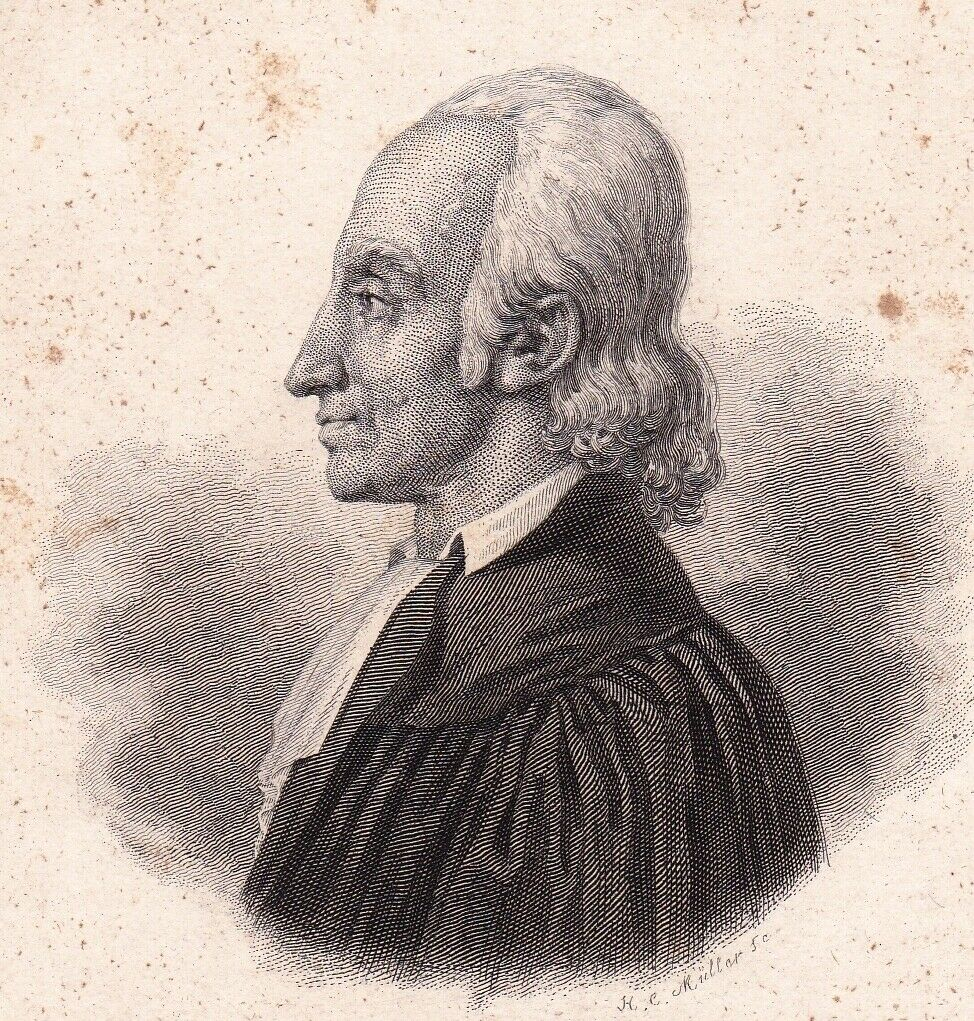

Johann Friedrich Oberlin is well-enough remembered to have an American college and a Japanese university named after him, not to mention countless streets in Alsace and a museum in his old home. But if any saint proves the point that no one can be a saint in isolation—that saintliness is a communal activity—it’s Oberlin. To remember this saint rightly is to bring back to remembrance the other less famous saints surrounding him as well.

It was not Oberlin but Jean-Georges Stuber who was a pioneer in the destitute parish of the Ban de la Roche, or “stone valley,” in a deep and isolated pocket of the Vosges mountains to the west of Strasbourg, France. Though these two pastors arrived more than a century after the Thirty Years’ War, the community still bore the scars of the devastating conflict and had never recovered. No road reached the village of Waldersbach or the other nearby hamlets, and no bridge crossed the fast-flowing Bruche River. The only schoolteacher was a man who had grown too old to look after his pigs anymore. The previous pastor hadn’t seen or used an actual Bible in more than twenty years. The soil was depleted, the yield of the farms was poor, and the people just barely managed not to starve.

Stuber took the post in the Ban de la Roche twice, serving a total of fourteen years, before he finally relented and accepted a more prestigious call to the St. Thomas Church in Strasbourg. He had laid the groundwork for the community’s renewal by finding a better schoolteacher, creating primers to instruct in reading, and preaching repentance and faith in Jesus Christ. But the Ban de la Roche was the last place anybody wanted to go; it was perceived more as a punishment than a parish. In the end, only one man was willing to take such a humiliating call as a worthy way to serve God: Johann Friedrich Oberlin.

One of nine children, Johann Friedrich grew up in a loving family in Strasbourg. They spoke German with each other but learned French quickly through a tutor, and Johann’s brother Jeremias Jakob went on to become a prominent linguist, codifying the patois spoken by the villagers in Johann’s parish.

Johann Friedrich was a pious child from the start, deeply influenced by Moravian Pietism and experiencing the “new birth” in early adulthood. He studied theology at the university and even got ordained, but he didn’t take on a church at once, feeling he wasn’t yet ready for it. Instead he became a private tutor to a doctor’s family, where he providentially learned the basic principles of medicine and veterinary science. When Stuber came and asked him to take up the ministry in Ban de la Roche, Johann was serving as a military chaplain. The younger man consented and was honorably discharged from his duties. He arrived in Waldersbach on March 30, 1767, twenty-seven years old.

His welcome was not a warm one. A posse promptly formed with the intention of waylaying and beating up the pastor, assuming that would discourage him enough to send him on his way. Instead, Johann Friedrich, getting wind of the coming siege, preached on Matthew 5—“turn the other cheek”—and after worship presented himself at the chief conspirator’s home, willingly delivering himself into the hands of his would-be persecutors. They were so astonished and ashamed that they apologized profusely and never troubled him again.

The young men of another village had a similar plan, in this case to give him a dunking. So the new pastor preached on the absolute confidence of the believer in the face of all harm, and instead of riding his horse he walked home. Such utter calm intimidated the vigilantes and they let him go in peace. Many such tales could be multiplied: Johann Friedrich never feared anything, his enemies least of all.

Shortly after his arrival in Waldersbach the pastor gained a helpmeet, the redoubtable Madeleine Salomé Witter. A friend of the family, she stopped in for several weeks’ visit at the parish. Johann Friedrich initially entertained, and then rejected, any thought of her as wife: she was accustomed to a higher standard of living than he’d ever be able to provide in the primitive village, and he judged that their “dispositions” didn’t quite match up.

However, just two days before her planned departure, an internal voice prompted Johann to “Take her for thy partner!” He was skeptical, but the voice persisted. So he put it to her the next morning rather frankly: “You are about to leave us, my dear friend; I have had an intimation that you are destined to be the partner of my life. If you can resolve upon this step, so important to us both, I expect you will give me your candid opinion about it before your departure.” She blushed and took his hand, and they married on July 6, 1768. They lived happily ever after, though not for as long as either might have liked. Madeleine died suddenly only a few weeks after the birth of their seventh child, though Johann Friedrich continued to see her and converse with her in visions for years after her death!

With the mother of the children gone, a young woman named Louise Scheppler who had already lived with the family eight years after being orphaned took over care of the household. She refused any salary. On occasion the pastor tried to pay her through indirect means, but she always figured him out and refused the money. On New Year’s Day, 1793, she wrote him a formal letter asking him to adopt her and consider her his child in every respect, which he gladly did. Before he died she took his surname for her own as well. By all reports the Oberlins were a happy family, even after Madeleine died. Their father even saw to it that the children rotated around the table so all could have a chance to sit next to him.

In the meanwhile, there was no end of work to do. With two services on Sunday, plus catechism for children and prayer services for adults, Johann Friedrich began the long slow work of re-evangelizing his parish. He preached warmly from the “dear Bible,” emphasizing the generous fatherhood of God, salvation offered through Christ, and the warm welcome awaiting every penitent sinner. Those who strove for sanctification would be strengthened by God, and this was in turn the basis for the powerful message of solidarity proclaimed to the congregation. Their pastor exhorted the townspeople not to buy frills for their own children’s clothing when other children in town lacked any clothes at all; he asked those with extra hay to share with those who had none. He didn’t shy from warning them about the final judgment, and once he broke up a mob harassing a Jew passing through town, rebuking them sharply: the Jew may lack the name of Christian, but all of you lack the spirit of a Christian.

The social solidarity of the town and parish meant that Johann Friedrich’s ministry turned toward the physical and economic needs of his people as much as the spiritual ones. His first project was the roads, long since abandoned; even the less official paths were marred by the constant rockfall and winter snows. A road would mean a market, a market would mean a living for the parish. He proposed to the locals that they all get together and hew rock to shore up a wall alongside the river, over which the finished road would traverse. They, disbelieving such an ambitious plan, refused to have anything to do with it. Undaunted, Johann Friedrich set to work by himself. Soon the invited men joined in after all, others showed up to help, and money and tools started arriving from Strasbourg. The workers reinforced the wall and diverted the river from the danger zones. The crown jewel was a wooden bridge, and today’s modern replacement is still called Le Pont de Charité, “Charity Bridge.”

The next step was to establish a lending “library” of farming tools to replace the primitive implements cobbled together by the villagers, and to rebuild their cottages along with cold cellars to store root vegetables through the winter. But the vegetables themselves were a problem. Poor field management had drained the fields of their fertility, and the variety of potato they grew was less fertile with every passing year. Johann Friedrich introduced a new strain of potato as well as methods of grafting to improve the output of the fruit trees. These, like most of his innovations, were met with severe skepticism until the villagers saw with their own eyes the lush harvest he reaped.

A favorite biblical verse of the pastor’s was “gather up the leftover fragments, that nothing might be lost” (John 6:12)—which seems as well as anything to illustrate his passionate ministry for a despised and neglected parish of the poor. Invoking the verse for practical application, he taught the villagers how to compost effectively, including old woollen rags and shoes, to increase the amount of arable land. He founded an Agricultural Society in 1778 for the most accomplished farmers in town, awarding a prize for the best ox. In connection with the Society he began the practice of delivering two-hour lectures on agriculture every Thursday morning. But even under the best management, the Ban de la Roche was not a great locale for farming, so Johann catalogued all the edible local plants and taught the people to forage.

Alongside infrastructure and agriculture, the pastor applied himself with equal passion to the matter of education. He started work on a schoolhouse despite a lack of funds, believing that anything he asked of the Father in faith that was truly right and good would be met with a positive return. Strasbourg patrons donated money and the villagers gave their labor, and in time all five villages came to have schools. Initially Johann Friedrich had to pay the parents for the lost labor of their children to get them to come to school but as usual, in the end, the parishioners acceded to the wisdom of his ways.

His most memorable innovation, however, was not the schooling for older children according to the usual standard but the establishment of nursery schools. In a community where the people were just scraping by, the children were left to look after themselves while the adults tried to eke a living out of the earth. As such the little ones were barely civilized, minimally articulate, and subject to terrible accidents. Johann Friedrich was at a loss as to how to change the situation until in 1769 he stumbled upon one Sara Banzet, another key player in Oberlin’s ministry.

This young woman had made a habit of inviting local children to her warm kitchen and teaching them useful skills such as knitting, all the while speaking and instructing them in general knowledge and biblical stories. The pastor was greatly impressed—and, unusually for his time, gave Sara the credit for her innovation even while he built on it, respecting the unique gifts that women brought to the vocation. He found and employed other young women such as Anne-Catherine Gagnière and his own adopted daughter Louise Scheppler to develop the pedagogy of the schools. Not only were the children kept out of harm’s way, but they came into the elementary schools better prepared and better students. Kindergarten as we know it has its origins in Ban de la Roche. Sara, sadly, died only five years later, never seeing the seed of her idea grow into full bloom.

Even during the upheavals of the French Revolution, Johann Friedrich managed to keep the peace in his isolated valley. In 1789 all of France’s clergy were deprived of their income. The townsfolk, fully conscious at last of the blessing they had in him, took up a collection, but all they could manage was 1133 francs as compared to his usual 1400 annually, and the following year they scraped together only 400. But their pastor made do on what they had for him and refused to charge extra for weddings and funerals, as many other clergy did. When Christian worship was forbidden by the revolutionary state, Johann responded by creating a Republican Club and holding meetings at which prayer, preaching, and the Lord’s Supper took place. Even while many other clergy, both Catholic and Protestant, were being charged and sentenced, Johann’s undeniable charity work earned him commendations from the government, including the famously controversial Catholic priest Abbé Grégoire. Johann had always been dedicated to the public good, and insofar as the Revolution also embodied this spirit, he gladly supported its ideals.

The reign of terror ended in 1795 and churches were allowed to reopen. Johann Friedrich renounced his salary—given the extreme poverty that his church had fallen back into, and the lack of wider church or state support—saying that only those who had something extra to offer need do so. To compensate, he took in pupils and used their fees to finance the parish. In fact, after reading about the tithes in Leviticus and Deuteronomy in the 1790s, he decided to give three tithes out of everything he earned: one for the needs of the church, one for the maintenance of the community, and a third for the poor.

It’s impossible to enumerate all of Johann Friedrich’s projects and accomplishments. He wrote and published an almanac for family use full of practical advice. He encouraged the celebration of baptismal birthdays. He required confirmands to plant two trees before they could be admitted to the rite and always exhorted his congregants to plant more. He established a festival in which first fruits were presented at the church. He built a tiny printing press to generate cards printed with Bible verses, of which he distributed tens of thousands over the years, often with a personal message inscribed on the back. He developed industries to employ the locals outside of the farming season: straw-platting, knitting, dyeing, and ribbon-making.

Johann Friedrich never traveled farther from his home than Fribourg and Saint-Dizier—never even as far as Paris. He had entertained the thought of taking a post in Pennsylvania until the Revolutionary War broke out and prevented him, and from then on he determined to stay in Ban de la Roche for the rest of his life. But that by no means deprived him of interest or energy in the wider world. He became the first French correspondent with the British and Foreign Bible Society, helping them put ten thousand Bibles into circulation in France. As soon as he heard of foreign missions, he sold all his silverware to support a missionary society. When he learned of the terrible condition of slaves in the Caribbean, he resolved never again to consume either coffee or sugar, since these were cultivated through slave labor.

In his old age, Johann Friedrich handed his ministry over to his son-in-law. Nevertheless, he continued the habit of opening the church’s baptismal register and praying for every single soul in the parish by name. He died on June 1, 1826, after a brief illness, and was buried in one of his parish villages, Fouday, where the townsfolk engraved on his tombstone words that capture perfectly his ministry to them and their love for him: Papa Oberlin.

Already in his life Johann Friedrich was acclaimed a great man, but he always turned attention away from his own accomplishments. “I have little merit in the good I have done; I have only that of obedience to the will of God. He has been graciously pleased to manifest his intentions to me, and has always given me the means of executing them.”

For Further Reading

Luther Halsey, Memoirs of John Frederick Oberlin, Pastor of Waldbach, in the Ban de la Roche (New York: Robert Carter and Brothers, 1857).

Loïc Chalmel, Oberlin: Le Pasteur des Lumières (Strasbourg: La Nuée Bleue, 2006).

Musée Jean Frédéric Oberlin in Waldersbach, Alsace, France